How did this project start? Were you previously aware of the Headwaters?

Paul Colangelo:I first heard about the Sacred Headwaters when a woman named Ali Howard decided to swim the entire length of the Skeena River—355 miles in 44-degree water over 28 days—to raise awareness and unite the downriver communities. I travelled to the Sacred Headwaters to meet Ali and photograph the start of her swim.

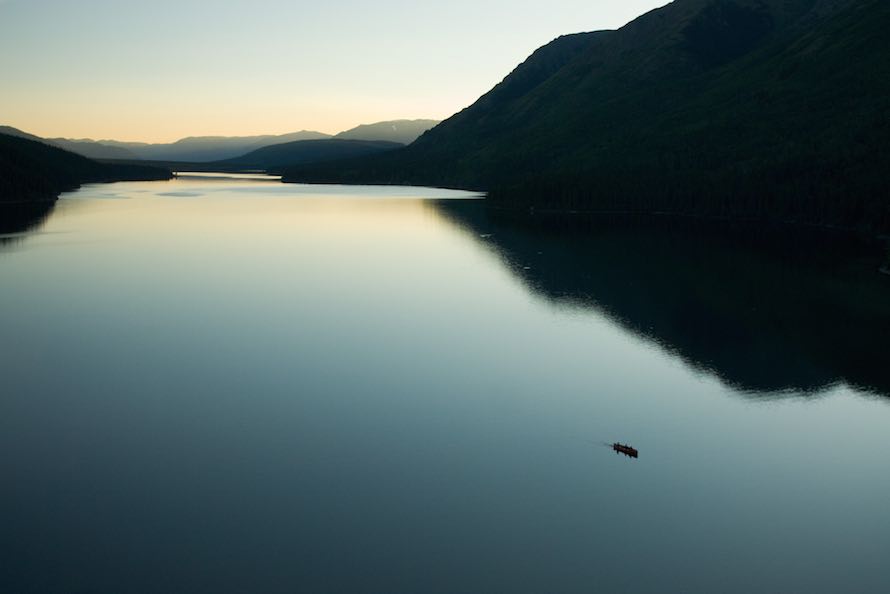

When I saw this place for myself, met the people who live there, and heard what it means to them, there was really no choice but to get involved. A number of organizations were running campaigns on the issue, but because the region was relatively unknown, there were not many images of it. Without images, people couldn’t emotionally connect to the place they were being asked to protect. For the next six years, I worked on telling the stories of the Sacred Headwaters, from the headwaters to the coast.

TMN:What’s the current protective status of the Sacred Headwaters?

PC:It’s actually pretty sad. For nearly a decade, the Tahltan people and their supporters fought to protect the Sacred Headwaters from a million-acre coal-bed methane development. In 2012, they actually won—a small, remote community took on one of the world’s largest corporations and won. But less than a year later, another company proposed a coal mine in the very same spot, so the Sacred Headwaters is once again at risk. There is also Red Chris mine, an open-pit gold and copper mine on Todagin Mountain owned by Imperial Metals, the company that is responsible for the Mt. Polley mine disaster in British Columbia, in which a tailings pond failed and flooded into salmon habitat. So although there was a big win for the Sacred Headwaters in 2012, I think the long-term outlook is poor. The completion of the Northwest Transmission Line, which extends the provincial power grid to the region, will usher a new era of development in the area.

TMN:What were your creative goals at the outset?

PC:The bigger goal was simple: Get the Sacred Headwaters into the homes of those who would never see it for themselves. This simple goal obviously had political roots—to make people aware of what was happening in this remote corner of the world, and hopefully spur them into action.

Creatively, the goal was to convey how vast, pristine, and dramatic this landscape is. This first stage of the project was meant to introduce people to the Sacred Headwaters, and it set the scene for the stories that followed. I began focusing on specific stories, such as the herd of Stone’s sheep on Todagin Mountain, and the Nisga’a eulachon fishery at the mouth of the Nass River.

TMN:Tell us about the sheep. How were they as subjects? You lived with the herd for three months.

PC:In total I spent about five months living on that mountain—four months over two summers and one month in the winter. The “Surviving Todagin” project was one of the most intense experiences I had. After living in that landscape by yourself for that long, you become just another member of the mountain’s community.

It was me, 250 sheep, a pack of 16 wolves, and roaming grizzlies. The mountain is an open plateau, so you can see for miles—they can all see each other for miles, and they know one is trying to kill the other, but a kind of equilibrium is struck where they learn their buffer zones and continue going about their day as long as that buffer isn’t breached. So there’s this eerie dynamic where predator and prey are within sight of each other, one just waiting for an opportunity.

The sheep are very skittish, so often I would spend the entire day following a small band of sheep to get them used to my presence before they would allow me to approach. And after weeks of this, you start to recognize some of the more distinctive individuals, and you can notice them growing more comfortable with you as the days go by.

Living on the mountain on my own for that amount of time was hard. There were these frequent wind storms that sent my tent sailing a mile down a valley. And if I anchored it down too much, it just snapped the poles. There were a lot of sleepless nights in a tent that was like a paint shaker.

TMN:As a conservation photographer, how much of your process is “hurry up and wait?”

PC:A lot of research and planning goes into these trips. You have to know what the important parts of the story are and how to illustrate them. And when working in remote locations, there’s often a lot of logistics to sort out. But once I’m in the field, the plan turns into more of a guide—it’s just as important to be completely present and willing to abandon preconceived ideas and go with what’s happening in front of you. So you plan the big picture, but then you have to capture the spontaneous moments that illustrate the story.

TMN:Is that when you feel your most unsure?

PC:On the first day of an assignment, I have this nervous energy. I’m switching gears from research and planning to being in it and shooting. It’s that empty space that exists before you get into the groove of the story and the images start coming together.